The mandala, as a schematic circular image used to assist in meditation, is found not only in the traditions of the East. Although we know that mandalas are used by Buddhist monks, the mandala motif can be observed in almost all cultures. In Christian churches, meditation considerations are literally lit by the light shining from stained glass rosettes, which are identical to mandalas. The cross-cultural pronunciation of the mandala is harmony and universally understood perfection. Working with a mandala does not have to propagate any religion, philosophy or ideology. It promotes harmonious beauty and constant work on oneself, inspired by tireless concentration similar to that observed in Buddhist monks during the act of creating a mandala.

A circle with the marked central point that primarily expresses the centre and everything related to it. People have always tried to express the universe as a circle, to enclose what is important in it. The word mandala comes from the ancient language of the Indian subcontinent and means: circle, wheel, disk, ring, orbit, centre, sacred circle, closed part of space where something happens, everything round, everything contained within certain limits, round shape, round image. The word mandala, taken from Sanskrit, is used in an unchanged form in many languages today as a term for an artistic motif in the shape of a circle. The root word itself suggests a region of the world where this motif was particularly cherished, and for this reason it is necessary to get to know the mandala motif in the eastern sense.

Mandala in Buddhism

The circular drawings are not assigned to one culture or religion, however, especially the Tibetan Buddhism, emphasizes the role of the mandala strongly. Before the introduction of Buddhism from India the culture of Tibet was underdeveloped. Buddhism caught on very well in Tibet because it did not supersede anything that was present there before. The mandala may be traced back to Tibet, to its monks, who starting from the eighth century created mandalas in form of paintings, three-dimensional objects, including architectonic structures, and images poured from coloured sand, grains, flowers or powdered gems. Traditional Tibetan mandalas are diagrams on the plan of a circle with squares inscribed in it, and this combination of geometric figures in Buddhism is not only aesthetic. The circle as a geometric figure that has no beginning and no end is a symbol of what is infinite and outer, the square symbolizes the four sides of the world, it expresses what is human and earthly. Everything is united at the central point, at the meeting point of transience and eternity. Traditionally, the colouring of the image begins from the inside. Tibetan mandalas are artistically rich, created according to precise rules and related to Buddhist philosophy. Apart from geometric patterns, they may also include images of a deity or deities. Mandalas in this culture are not limited to static forms only. Mandalas can be the basis of rituals, the most famous and spectacular is to create a large diameter mandala for many days and then destroy it. It is worth noting that a few or a dozen monks participate in such a mandala creation, which additionally arouses admiration for the harmonious cooperation of its creators. The meaning of this ceremonial is the ephemeral life, awareness of not only the objective but also the path leading to it, and being mindful of the present moment.

Mandala in therapy

The Western world with its highly developed culture perceives mandalas rationally. It gives the mandala its symbolism. Carl Gustav Jung, Swiss psychologist and psychiatrist, as well as a versatile scientist, researcher of cultures and religions, saw for the first time the potential of using mandala in the process of patient therapy. This outstanding twentieth-century thinker also practiced mandala drawing, noting that in the process of creating, internal contents emerge. According to Jung, who popularized mandalas in Western culture, this motif is a symbolic expression of what resides inside a human being. For a Western, extroverted society that is lost in consumerism, mandalas are a creative way to regain contact with what is inside, what is neglected and unconscious in man. For this reason, creating a mandala and analyzing it is called a letter from yourself to yourself. Mandalas can be a creative attempt to order all thoughts, give meaning and a point of reference. The use of the mandala theme in Western culture is not a blind imitation of the Eastern spiritual practices. The harmonious shape of the mandala is natural and close to man, which is why the mandala has appeared in art therapy, in the technique applied for work with children, adults, the sick and the healthy. Working with a mandala drawing gives is the technical freedom to freely rotate the sheet and colour it without losing the sense of the whole picture. Colouring of ready-made mandala templates is popular all over the world. In this form, we do not need to create a mandala from scratch, or even analyze it, as Jung did. It focuses more on mindfulness-based art therapy, which does not judge, but accepts the sensations and thoughts that are flowing at the moment of creativity. On the one hand, we are dealing with the therapeutic effect of the act of colouring, on the other hand, with a graceful motif with repetitive patterns that radiates beauty and perfection of form. The benefits of communing with the mandala were applied in the VR TierOne therapy dedicated to patients with depression, anxiety, following a heart attack, stroke and COVID-19, who experience a decline in their well-being. In the virtual world , mandalas strengthen the human interior with the language of shape and colour. Linked with metaphorical messages, they help focus attention and experience being “here and now”. The immersive virtual world helps us maintain the state of mindfulness. The applied metaphors and symbols are more than their simple reality indicates, they encourage insight, reflection, and strengthen the positive message of the virtual therapist. We noticed that colouring the mandala helps to relax, reduce anxiety and tension, and maintain attention and concentration. Keeping mindfulness promotes well-being. The Virtual Reality experience can be continued by means of traditional colouring of the specially designed VR TierOne therapeutic colouring book. A coloured mandala can be a memento of the moments lived, a diary of the patient’s emotions and reflections related to virtual therapy.

Mandala in nature and art

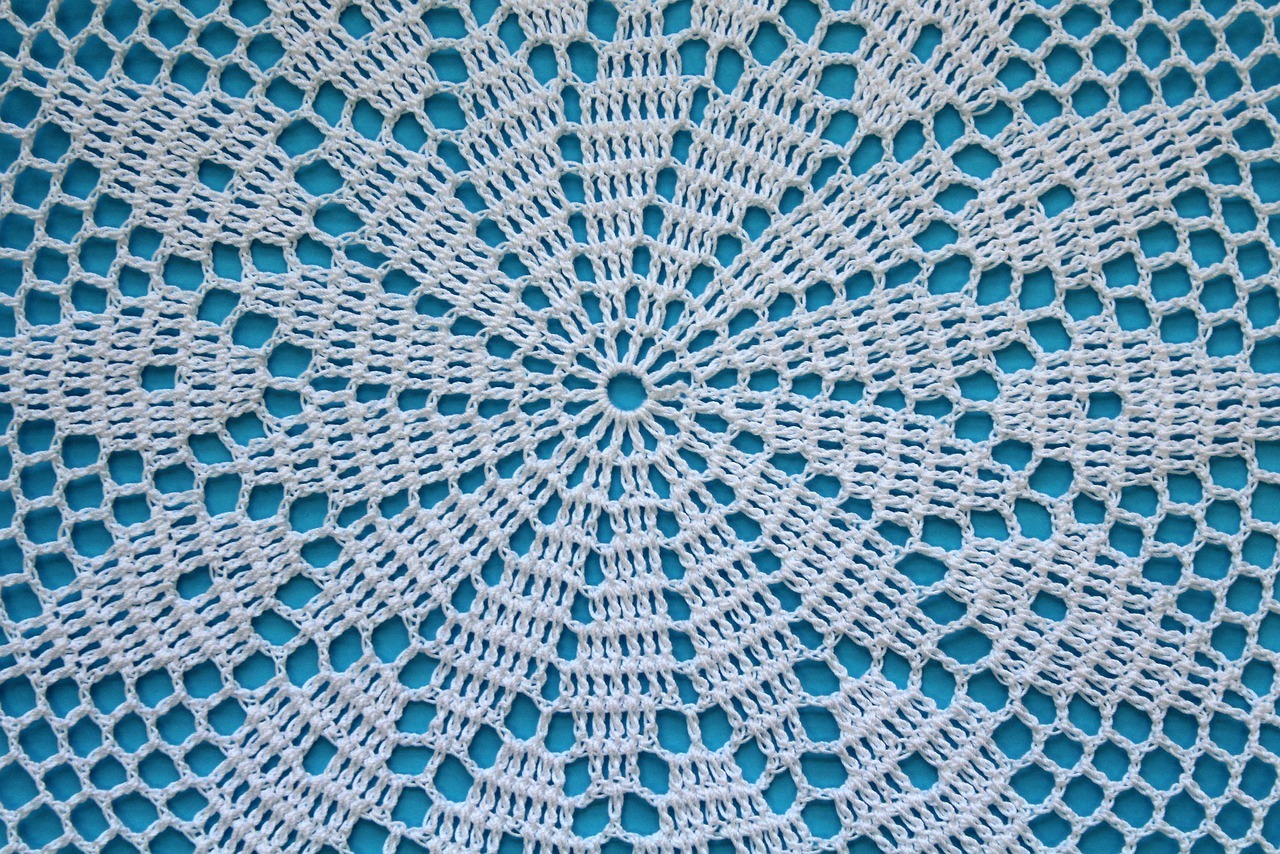

We can find the basic pattern of the mandala in nature. Flowers, spider’s webs, snowflakes, eye irises, fruit and tree cross-sections are all mandalas. In art, mandalic forms are recognized in European sacred stained glass windows, Indian dream catchers, round crochet or lace napkins, round tapestries and well-known Polish cut-outs in the form of a circle. Cutting, crocheting and embroidering are, just like colouring, a form of meditation and a way to relieve stress, with the difference, however, that colouring is based on skills that everyone possesses since their childhood. The remaining ones must be learned first. Even if we do not master the tools and sequential handicraft movements, we can still commune with the finished products of artists. The mandala motif became popular in art therapy, because the symmetry of the mandala gives aesthetic pleasure to both its creator and recipient.

Mandala in nature and art impresses with symmetry and intricate pattern.

Both in nature, and in art, the perception of the mandala motif introduces harmony in the human being. A circular order characterized by repetition can be found in the natural cycles of the day and seasons. Similarly, in the VR TierOne therapeutic cycle, we can find harmony and strengthen life-giving forces. The mandala motif can be understood as the compositional idea of imagining what is important through a drawing on the plan of a circle, which was repeated in many cultures. It is an attempt to enclose infinity in a finite form. Mandala is a beautiful timeless theme. It is simple in its design and rich in patterns. The strength of the mandala motif results from its omnipresence in the micro and macrocosm.